Visit La Ca’ Granda

The promise made by Francesco Sforza (1401-1466) in 1451 to the people of Milan to establish “a large and solemn hospital” led to the decree proclaimed on 1 April 1456. The experience of the Communitas ambrosiana (1447-1450) had marked the final demise of the ruling dynasty of the Viscontis, and when Francesco Sforza triumphantly entered Milan he found a city that had been reduced to misery. In subjecting themselves to the new lord, the people of Milan hoped to obtain peace, stability and prosperity. They called upon the Sforza not to focus exclusively on strengthening his rule but also on reinvigorating Milan’s vocation in providing assistance to the needy as part of a tradition the city had developed over the centuries.

Shortly after the decree was issued, following the required official endorsement by pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, 1405 – 1464), the duke Francesco Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti, his wife as well as staunch backer of the Sforza’s policy in providing assistance, laid the foundation stone of the hospitale grando, the “big hospital,” that by incorporating the administration of sixteen hospitals operating at that time in the city earned the appellation of maggiore, or “major.” Thanks not only to the quality of the services it provided to patients from all extractions and provenance, including non-residents and foreigners, but also to its ability to attract voluntary workers as well as donations from benefactors, the hospital was soon being acknowledged as the Ca’ Granda de’ Milanesi, the “Big House of the Milanese”.

The project was initially entrusted to Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469), who sought inspiration from the potent symbol of the cross. The layout involved two crossbars, one for men and the other for female patients, developing within a square, each defining four square-shaped inner courtyards. The two larger blocks were thus connected by a large rectangular courtyard at the centre of which stood a church. The project underwent significant changes as the original architectural solutions had to be adapted to the rigours of the local climate and also scaled down as a consequence of the chronic lack of funds, that slowed down work to such an extent that construction was terminated but a few centuries later.

Not only factories, train stations, strategic military targets, the allied bombing of Milan in the period between October 1942 and August 1943 hit those sites that the population most related to, namely religious buildings, artistic and cultural monuments and even schools and hospitals, including, of course, Ospedale Maggiore.

The bombs that rained down between 13 and 16 August 1943 brought down part of the façade along via Festa del Perdono, destroyed the Central Courtyard, including the portico, and heavily damaged the lateral cloisters. The restoration of what could still be salvaged was due, above all, to the efforts of a great Milanese architect, Liliana Grassi (1923 – 1985), who not only reinvented what had been irremediably lost but also relied on a variety of techniques depending on the nature of the reconstruction work that was required.

The initial phase of the work focused on the rearrangement of the 19th century wing – the teaching wing – where a more creative approach was possible because the artistic value there was less significant than in the rest of the monument. The reconstruction through anastylosis of the Central Courtyard proved to be far more challenging and was ultimately terminated in 1958 with the inauguration of the Università degli Studi. As for the 15th century wing, work started in the 1960s focusing especially on the four cloisters. The delicate restoration work in this part of the edifice, as well as the reconstruction ex novo of several sections, relied on a sound methodology based on the rigorous analysis of contemporary documentation and iconography that allowed for the preservation of the original construction patterns. Architect Grassi’s work officially terminated on 31 October 1984, with the handing of the Crossing to the university.

Designed by Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469) in a layout consisting of three main bodies, the Ca’ Granda was left unfinished for a long period of time, until, that is, a very conspicuous bequeathal gave to the construction its long-awaited turnaround. In 1624, following the death of the tradesman and banker Giovanni Pietro Carcano, the hospital received half of the interests arising from his assets, a very consistent annual sum that was paid out for sixteen years in a row. Thanks to Carcano, who is remembered as the Ospedale Maggiore’s “second founder”, Filarete’s monumental complex was redeveloped and expanded.

The work initiated with Carcano’s cash principally involved the Central Courtyard, or the Cour d’Honneur, also named after Francesco Maria Richini (1584 – 1658), one of the architects involved in the redevelopment effort. The 17th century project had to take into account what had already been constructed over the previous centuries, namely the quadrilateral built at the time of the Sforzas (the win on the right) and the portico that connected it to the Central Courtyard Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (1447 – 1522) had almost finished by 1497. The 17th century work, which relied on the guidelines set out in the Filarete model for all four sides, completed the Central Courtyard starting from the entrance side. Work then proceeded along the front – where the construction of the Annunciata church started in 1635 – and, finally, on the right-hand side, where the portico was renovated, maintaining, however, the pre-existing decorative patterns.

Work at the Crociera (Crossing) on the right – reserved, as the one on the left, for patients – started in 1459 and was terminated in 1465 under the supervision of Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469). The foundations were in sarizzogranite, as the columns, and hosted service facilities, namely cellars, storerooms and workshops. Each arm had a name. The first to be built – perpendicular to the Naviglio – was dedicated to Bianca Maria Visconti and reserved to female patients. The entrance portal was decorated by a stone lunette depicting the Annunciation (1463-1465) by Cristoforo Luoni.

The arms of the Crossing were all endowed with acquaioli (stone washbowls) all having metal basins and buckets. Provided, right from the outset, with a sewerage system, the Crossing had toilets, which were called necessaria (“necessaries”) or destri (“nimble”). Among the priorities duke Francesco Sforza (1401 – 1466) had set were, in fact, the construction of an adequate number of toilets – one for every two beds – that Filarete envisaged being served, both horizontally and vertically, by running and rain water to ensure maximum and constant hygiene. Heating was provided by three huge chimneys. Alongside each bed was a small wall opening that acted as a cabinet and as a small table thanks to a wooden folding easel.

In 1472, duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1444 – 1476) ordered feather mattresses to be placed on the beds, and a year later patients started to be admitted for hospitalisation. The blankets were in leather and the sick, one for each bed, were given mixed wool vests, shoes and white caps (1486). At admission, the sick were undressed, washed and combed. The beds, warmed in winter, were made twice a day, and twice a day the floors cleaned and the rooms aired. In warmer summers, halfway up the ceiling, wet sheets were hung. By the 1490s, the Ospedale Maggiore could host up to 1,600 people, including both sick and personnel. In a bid to optimise space, new halls were created by adding mezzanines, in the arms of the Crossing, which remained in use until the 19th century.

Designed starting 1456 by Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469), who conceived a series of sculptures in marble, stone and terracotta, the portico has conserved the original chromatic suggestions notwithstanding the fact that it underwent numerous changes even during the construction phase. The lower part of the façade up to the stringcourse storey demarcation can be attributed to the Tuscan architect. The basement hosted shops, stores and caneve or cellars. Along the portico were wooden lodges where surgeons and barbers operated and medicated the sick whose ailments did not solicit hospitalisation.

The portico featuring 29 rounded-arches that joined the Crossing was constructed between 1458 and 1462 by Lombardy craftsmen. In the arches’ intradoses, fragments of frescoed decorations – rhombuses and tondos – were brought to light. The terracotta arches were provided by Filarete himself who also made the decorative arch-shaped bands and the large and small tondos (1461). An arcade, not the central one, was designated as a vestibule of the mastra, or principal, gate and of the infirmary. To access it, a wide staircase was built, albeit with little practical sense.

According to Filarete – who was probably the author of the haut relief tondo depicting Francesco Sforza – it was Vincenzo Foppa who made the fresco on the portico with the scene depicting the laying of the cornerstone, while the Humanist Francesco Filelfo and the courtesan Tommaso da Rieti were the author of the epigrams still visible at the entrances of the Crossing. The upper floor was the work of the Lombard Boniforte Solari (1429 ca. – 1481 ca.), an engineer at the Fabbrica del Duomo, while the brother Francesco (1420 ca. – 1469) designed the 18 finely decorated balconies (1467). In 1597, the entire portico façade was shut with metal gratings, which gave to the corridor the name of Portico delle inferriate. In 1648, the central staircase was replaced by side ramps, which were entirely dismantled at the end of the century when access to the infirmary was ensured from the Central Courtyard (1686).

Designed by Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469), the Cortile della farmacia (The Pharmacy Courtyard), although it was the first to have been constructed under his direct supervision between 1463 and 1467, was ultimately terminated by Francesco Solari (1420 ca. – 1469), brother of Boniforte (1429 ca. – 1481 ca.), with the help of the sculptors Guglielmo del Conte and Pietro Ambrogio de Munti, who made the columns and the capitals. Initially, the courtyard was designated to host the hospital’s administrative offices, among which the Chapter of the Deputies whose task was to handle hospital administration. It is likely, the pillars located in this exclusive location were covered with elegant decorations as can be observed by the traces of surviving framed graffiti depicting vases, endowed with curves in the shape of snakes, on whose rim birds are perched.

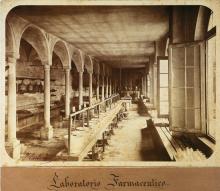

Work on the administrative area, which included the offices of the notary public, of the accountants and of the archives, was terminated with the construction of a hall, with fireplace (1468), that probably served as the capitulary. This was followed by the construction in 1502 of a refectory that was successively decorated by a mediocre reproduction of Leonardo’s Last Supper. It is likely the bread store was just next door. There also was, in the south-western corner, a well, whose curb was probably made by the sculptor Giorgio Gariboldi (1464). In the second-half of the 17th century administration was moved elsewhere and the premises it vacated were for the most part used by the pharmacy (laboratories, storerooms and storage rooms) including the green space at the centre, which was transformed into a small botanical garden.

The earliest mention of medicinal activities being carried out at the Ospedale Maggiore goes back to 1458 when Giovanni Vailati was appointed magister aromatarius. But it was only in 1470 that a formal agreement was signed authorising the opening of two chemist’s shops specialising in the administration and preparations of medicines exclusively for hospital patients. The finishing work of the decorations in the second pharmacy were entrusted to Stefano Cittadini in 1497.

Designed by Filarete (Antonio Averlino, 1400 – 1469), who personally supervised the works from 1460 to 1465, the Cortile dei bagni (The Baths Courtyard) was completed by Boniforte Solari (1429 ca. – 1481 ca.). Initially, the courtyard was reserved for the recovery of the aristocrats, who paid for their stay at the hospital, and was called the “gentlemen’s courtyard.”While successively renamed the “women’s separate courtyard” as it was principally reserved to labouring women (the area around the San Nazaro church), it was also designated to the “scabbed”and the “delirious”of both sexes (the area by the portico), for it afforded a degree of isolation compared to the overcrowded wards of the Crossing.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the area was turned into the “servants’ courtyard” reserved to nursing staff and attendants. The courtyard had a wardrobe (by the portico) and a wash-house (by the San Nazaro church). A surface well was located in the north-eastern corner, while a system of baths was constructed at the centre of the courtyard starting from the 18th century. The bathing complex had separate pools for men and women and, starting from 1802, also half baths that allowed partial immersions. These served for hydrotherapy and were located in the infirmaries.

The work of Lombardy craftsmen, the Cortile della ghiacciaia (the Ice-House Courtyard) was a development of the project Filarete had started in 1486 when the hospital Chapter ordered the purchase of stones and other materials for the construction of the adjacent courtyard, successively knows as the Cortile della legnaia (the Woodshed Courtyard). Originally, the courtyard hosted a cemetery built, in 1473, by the master mason Ambrogio da Rosate at the back of the first chapel. The altar was initially placed where the crossbars met so that it could be viewed by all patients, so that they could assist the liturgical functions as was in the tradition of the ancient hospitals of the knights hospitaller of Jerusalem (present day Order of Malta). Successively, the chapel and burial yard were shifted, replaced by the apothecary’s workshop that was, in turn, transformed into the dispensary.

The ice-house, located in the central part of the courtyard, is mentioned for the first time in November 1638 as the cella nivaria, the “snow cell”. The reservoir was filled in the winter months with snow, which, appropriately pressed and wetted, was allowed to freeze and used to preserve perishable food and, possibly, also therapeutically to cure traumas, fevers, inflammations, gouts, etc. The exterior of the reservoir was surrounded by a semi-circular corridor that acted as a dispensary as well as a brick casing.

The ice-house was managed by hospital staff. A surface well, originally serving the apothecary’s workshop and built by Boniforte Solari (1429 ca. – 1481 ca.), was located in the south-western corner (1472). Overlooking the courtyard was possibly the old wash-house (1499), which could rely on an independent water conduit, and a mill, constructed between 1519 and 1523 along the Naviglio side, whose milling stones were found during the challenging post-war restoration campaign. The Ice-House Courtyard was, in fact, the part of the complex that was most damaged during the 1943 bombardments, and was fully restored in 1962.

Not unlike its twin – aka the ‘ice-house’ – the Woodshed Courtyard was the work of Lombardy craftsmen who sought inspiration from Filarete’s project and worked on it staring from 1486. While it was originally known as the “women’s courtyard” because it was reserved to female patients, by the 18th century it had come to be known as the “nizuola courtyard” probably because of the presence of a hazel tree, nisciœula being the Milanese word for “nut.” Successively it was renamed after the kitchens located along the eastern side. It was only starting from the second-half of the 18th century that we find reference to a “woodshed,” located within the perimeter of the courtyard and surviving until 1943. Wood was previously stored in the main courtyard, behind the tiny church and attached burial ground.

Archaeological digs carried out by the Università degli Studi in 1995 brought to light a large quantity of bones and animal horns, most likely the waste from the hospital’s slaughterhouse (built in 1494) or, more simply, from the kitchens or attached dispensary. It is likely this part of the edifice also hosted a panateram pristini, or bakery (built in 1478), a chicken coop and a pigsty (first mentioned in 1499) as well as a livestock slaughterhouse (existing since 1500). The practice of butchering livestock in the hospital, in fact, started from that date.

Within the central octagonal structure there once was a well having a diameter of 2 metres. It is not sure whether it was a surface well, from which water was drawn, or an underground sewerage well. A surface well for kitchen use, on the other hand, already existed in the north-western corner, made by Guglielmo del Conte in 1482.

The mortuary service at Ospedale Maggiore had been authorised right from the outset with the 1456 foundational papal bull issued by pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, 1405 – 1464) and provided within the hospital premises soon after the hospital began operations (1473). The area reserved as a burial ground, the Sepolcreto, expanded rapidly not only because those who died in hospitals were generally not allowed to be buried in the city’s parish cemeteries but also because those who were buried in the hospital grounds were granted indulgence.

On 7 May 1473, the Ca’ Granda Chapter decided to build a small wall, by the Annunciata chapel (1473-1587) originally located in north-western side of the present-day Central Courtyard, serving to delimit a space for the burial of the poor who died in hospital. The bones were successively laid in the original burial ground, probably underneath the chapel itself. During the 16th century, as the number of patients, and therefore of deaths, grew, the lawn in the hospital grounds was turned into a paupers’ grave, the foppone or “pit” in the Milanese dialect, were the bodies were buried. The foppone was periodically emptied and the bones placed in the hospital’s burial grounds, which were known as the brugna. In the 17th century another burial chamber was created. Known successively as the ‘Old Brugna’ it was located under the church’s crypt. Other sepulchres – the New Brugna - were constructed along the Naviglio side (now via Francesco Sforza), remaining in use until the end of the 17th century, as C14 testing on several samples has proved.

It was only starting from the last decade of the 17th century that the decision was taken to build a new cemetery outside the city walls. Known as Nuovi sepolcri (‘New Sepulchres’) and now as Rotonda della Besana, the burial ground was established in July 1697, but the Brugna vecchia, however, was never totally emptied.

Work started at the end of the 17th century on the construction of the new left-hand side Crossing, which was terminated between the 18th and 19th century thanks to Carcano’s bequeathal, a conspicuous donation, amounting to 2,265,000 lire, signed out by the notary public Giuseppe Macchi in 1797. Three out of the new four courtyards were made in a style different to that defined in Filarete’s original layout. The only exception being the one reserved to the Ca’ Granda rector and his family, which was architecturally similar to 15th century courtyards and known as the Quarto delle balie, the ‘wet nurse quarter’ because it was located in a separate and protected part of the complex, thus becoming the designated area for wet nurses where they could breast feed infants in full privacy.

Following its significant enlargement, the hospital could now, in fact, take abandoned and undesired infant under its wing, weaning them and successively rearing them so they could be adopted. The long-standing attention for abandoned children and the respect for the rearing skills of women in the healthcare sector, prompted the hospital to establish in the 18thcentury – in the Age of Enlightenment – an obstetricians’ school. Founded in 1767 by Bernardino Moscati and reserved for surgeons, the school was successively opened also to “co-mothers” and “wet nurses” (i.e. godmothers and midwifes) who were at least 18-years-old and “learned in reading and writing.” The illuminated reformism of the Austrians in a Milan that was ever more receptive to science and technique soon turned the Ca’ Granda into a “teaching and specialisation hospital”.

The links between the hospital and Milanese society were further strengthened during the Risorgimento, especially during the uprising known as the Five Days of Milan (18-22 March 1848) when hospital doctors, healthcare staff, both men and women, took part in the events either aiding the wounded from both sides or taking up arms, combating on the barricades for the independence of Lombardy from Austrian rule.